Greg Tate, Hip Hop Journalism Godfather, Dies At 64 – Here’s Why His Words Mattered

New York, NY – Over the past three weeks, the Black music and arts communities lost three pillars in Young Dolph, fashion guru Virgil Abloh, music impresario and “The Black Godfather” Clarence Avant’s wife Jacqueline Avant, and pioneering rap critic Greg Tate.

The latter two losses mentioned may not register as urgently in many younger Hip Hop fans as Dolph’s Southern rap radio hits and Abloh’s high-brow urban couture designs, respectively, which helped the culture’s pivot forward over the past 10 years.

Spokeswoman Laura Sells for Duke University Press, which published Tate’s essay Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader in 2016, confirmed his death at age 64 on Tuesday, according to NBC News.

In addition to Rocky Ford and Nelson George at Billboard Magazine at the dawn of the 1980s, Hip Hop’s original Bible The Source once dubbed Tate as “one of the godfathers of Hip Hop journalism.”

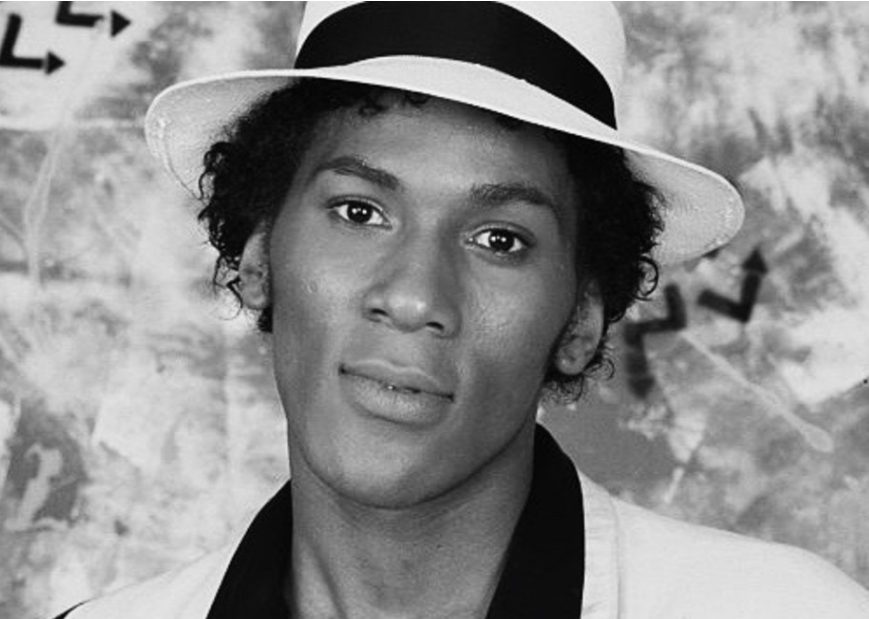

Tate was an author, poet, producer, a writer among writers. Nicknamed “Ironman” before Ghostface Killah adopted that alias for his debut album in 1996, Tate has appeared in countless Hip Hop documentaries since the 1990s.

Harlem’s music cornerstone Apollo Theatre paid tribute to Tate on its marquee upon the news of his passing. Also, a multitude of prominent Hip Hop journalists such as Jeff Chang, Noah Callahan-Bever, Dan Charnas, Touré, Harry Allen, Rolling Stone‘s Rob Sheffield and more paid their respects to Tate on social media.

#gregtate pic.twitter.com/lygZdjLwkS

— Tara Turk-Haynes (@ttarahaynes) December 8, 2021

Papa Greg Tate has joined the ancestors. The Godfather of hip-hop criticism. An expansive, gentle soul. His only violence was intellectual. (& it was beautiful & most of them folks deserved it!) He taught me/all of us so many things about so many things. Thank you, Greg. pic.twitter.com/5RL1c2Tggg

— Jeff Chang (@zentronix) December 7, 2021

Thank you for doing it all first, and so so well, Greg Tate. Rest In Peace and in Appreciation.

— Noah Callahan-Bever (@N_C_B) December 7, 2021

Greg Tate's prose was hypertext before there was such a thing—drawing on layers of references—and, today, no one can do with a hyperlink what he did in a world without them. He rarely put himself into the story: You felt his presence, but the focus was the *idea*, not the "I".

— Dan Charnas (@dancharnas) December 8, 2021

Damn…Greg Tate. He’s the blueprint. ?? Huge loss.

— Stretch Armstrong (@StretchArmy) December 7, 2021

I've had this Greg Tate piece taped up on the wall over my desk all these years: his Chaka Khan live review from the Voice, 1992. this is how it's done. "the only wail that matters, the roar & the resonance against which all contenders are judged." that was Tate, for all of us. pic.twitter.com/uTXe1WBA9M

— rob sheffield (@robsheff) December 7, 2021

Aside from his influence, and the generosity of his friendship, I'm most thankful I made the opportunity to tell him, at least a little bit, about the effect he'd had on me.

I hope his estate will publish the James Brown book he was working on, and that I'm sure bedeviled him. pic.twitter.com/GY5kuahgQ5

— Harry Allen (@harryallen) December 8, 2021

Just heard that my friend, my mentor, one of the greatest writers of his generation Greg Tate passed away last night. He was a genius and his writing was amazing and I learned a ton reading him. I’m so sad.

— Young Daddy (@Toure) December 7, 2021

Tate is largely responsible for how rap album reviews and editorial content are written and read on any Hip Hop publication. He narrowed the scope of that content from his original Galileo Galilei-style telescope. He was a genius in how he spotted rap stars in the urban space and expose them to his readers’ curious eyes, and discuss why they are there, where and how long they should navigate the sky.

Tate was initially hired as a freelance contributor by influential music journalist Robert Christgau at New York City’s cultural zeitgeist periodical Village Voice in 1981. Tate revered him because Christgau “believed Afro-diasporic musics should on occasion be covered by people who weren’t strangers to those communities.”

Tate’s incisive prose swung off pages and razor cut into his readers’ minds and dissected subjects like an Excalibur.

“It was like writing war dispatches right there on the ground,” Tate told Pitchfork in 2018 about his early days covering New York’s burgeoning Hip Hop scene after he moved there in 1982 from Washington. “There was all this incendiary work coming out. It was unprecedented. It didn’t sound like anything that had come before. There was a lot to talk about.”

Tate whetted his readers’ appetite by creating demand for his deconstruction of Black music and culture with an endearing, humorous wit and progressive coolness of a New York City East Village griot through 2005 when he left the Voice.

His primal influence was impactful on longtime editor and HipHopDX’s Head of Content Jerry Barrow.

“I didn’t know Greg personally, but he touched those who touched me,” Barrow told DX. “His name was spoken with nothing but reverence by those who molded me as young writer daring to walk in his shadow. He showed us that criticism could be sharp without wounding. Rather, his blade helped to whittle an industry out of passion.”

In Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018, Tate said about his early years at The Voice, “I was trying to literally approximate music on the page.”

He also wrote about R&B, soul, jazz and rock in The New York Times, Washington Post, and magazines including Rolling Stone, Artform, Down Beat, Essence, JazzTimes, and Vibe.

One of his greatest works includes his first book Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America in 1992, a collection of 40 essays addresses race, politics, music, and literature.

He radically wrote in Village Voice about Public Enemy, Eric B. & Rakim, late painter and rap record producer Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the racial identity of Michael Jackson.

“Rakim’s on an elocutionary speed-trip, a black bullet train slitting through hyperspace,” Tate wrote about Eric B. & Rakim’s 1988 album Follow The Leader’s title track. “The rhymes are telemetric, tracking sucker-soft targets with a monomania more relentless than anybody’s Terminator.”

Tate made Black rock musicians matter

The Dayton, Ohio-born and Washington D.C.-raised Tate didn’t just write about music — he wrote music as a respected guitarist.

Tate’s guitar was his shield of credibility in defense of his critiques as he embodied the adage “the pen is mightier than sword.” Tate helped prove writers are equally artistic as the subjects they cover, as long as they immerse themselves in the artform without designating themselves to deskwork.

Fellow esteemed poet, singer and activist Saul Williams tweeted his initial exchange with Tate at New York’s former landmark Bowery-based punk rock venue CBGBs about how Tate forced his way into being heard, not just read.

“My first gig at CBGBs, my band was setting up for sound check, Greg Tate walks in [with] his guitar and amp, walks right on stage and plugs in. He looks me dead in eye, ‘You know I’m in your band, right? Y’all ain’t traveling to space without me.’ And that was that.”

My first gig at CBGBs, my band was setting up for sound check, Greg Tate walks in w his guitar & amp, walks right on stage and plugs in. He looks me dead in eye, “You know I’m in your band, right? Y’all ain’t traveling to space without me.” & that was that.

— Saul Williams (@SaulWilliams) December 7, 2021

As Tate was writing about the Hip Hop’s underground beauty, he had an unremitting allegiance to retrieve Black rock and roll musicians’ rightful place as the genre’s gatekeepers in a whitewashed corporate infrastructure.

In 1985, Tate co-founded the non-profit Black Rock Coalition with hard rock band Living Colour’s guitarist Vernon Reid and producer Konda Mason. Their purpose was to fight Black artist stereotypes and form camaraderie for African-American rock-influenced musicians marginalized by record companies after Blacks originated rock music in the 1950s.

Some of the iconic bands and artists who’ve been part of the Coalition are hardcore punk progenitors Bad Brains, Chicago blues rock pioneer Buddy Guy, King’s X, Lenny Kravitz, Outkast, TV On The Radio, Erykah Badu, and Tate’s orchestra Burnt Sugar.

The Black Rock Coalition’s work has been a main artery to the psychedelic rock, jazz, funk and soul-infused subgenre “afro-punk” and the annual festival of the same name since its debut at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2005.

Longtime rap industry executive and A&R Dante Ross eulogized Tate on Instagram, mostly speaking about Tate’s seismic development of that scene. Ross called him “the most influential cultural critic of my lifetime” and compared Tate’s wordplay to a gifted MC.

View this post on Instagram

Today, the Black Rock Coalition’s impact and coverage of rap albums in globally circulated newspapers and on rap websites has given a space for hybrid rock, jazz, soul, funk and rap-focused artists from Anderson .Paak and Kendrick Lamar to Pink Siifu.

Tate was the grandfather who helped put that in place as he spoke Black America’s native language and kept his journalistic integrity to cover Hip Hop in its first village and throughout the world.